When it comes to what you can gamble on these days, all bets are off.

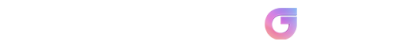

On prediction markets — platforms where people bet against each other on the outcomes of real-world events — traders are wagering on the chances of a major meteor striking Earth before 2030, whether Taylor Swift will mention her fiancé on her next album, and who TIME’s “Person of the Year” will be. As demand soars for the ability to bet on almost anything, prediction markets are processing billions of dollars in volume every week. Traditional players are taking notice: a number of financial giants and sports-betting firms are getting in on the action.

The relaxed regulatory environment under the Trump administration has fueled this growth and blurred the line between trading and gambling. Amid the rise of sports betting apps, novelty cryptocurrencies, and meme stock speculation, prediction markets are yet another way for amateur traders to rack up losses quickly. Critics say that thin oversight also leaves markets exposed to insider advantages that can undermine their integrity.

The sudden emergence of the industry in the mainstream is beginning to recast public life as a series of bets waiting to be placed. Here’s what’s important to know.

ALSO READ: Aurora Increases Gaming Limits, Creating New Competition for Illinois Casinos

What is the mechanism of prediction markets?

People can wager on the results of actual events on prediction markets like Polymarket, Kalshi, and PredictIt. Traders wager “yes” or “no” on a variety of events, such as the Democratic Party controlling the US House of Representatives the following year, Bugonia receiving an Oscar nomination for Best Picture, the Denver Nuggets winning the National Basketball Association Finals, or Chicago receiving more than 12 inches of snow this month.

This is a lot like internet betting, except unlike conventional gaming firms, there is no “house” that sets odds or takes the other side of your wager. When you purchase a “yes” or “no” share, also referred to as a “event contract,” another person on the exchange is selling it to you and placing a wager against you. In addition to matching buyers and sellers, the exchange retains the funds until the event. A “yes” or “no” share usually costs between $0 and $1. Supply and demand determine the price: Strong demand for “yes” drives up the cost of that side of the wager while driving down the cost of “no.” Strong “no” demands undo those shifts.

Traders who wager properly receive $1 for each contract they purchased after the event. Money is lost by those who wager on the wrong side. For instance, you would receive $1 back—a 60-cent profit (less fees)—if you purchased a 40-cent “yes” contract that said it would snow more than 12 inches. You forfeit the forty cents you paid if it doesn’t snow.

Courtesy: https://www.covers.com, https://www.casino.org, https://pechanga.net